A brief (and incredible) history of women’s football

We’re living through a golden age of women’s football. With more investment and public support than ever before, record and growing match attendances, ever-increasing mainstream media coverage, and fantastic levels of participation at grass-roots level, there’s plenty to feel proud of and hopeful about if you’re in any way involved with the women’s game. Raiders parent, Emma Weare, tells the story.

But to truly appreciate the momentum women’s football now enjoys, it’s worth taking a moment to consider its extraordinary journey. As with many modern movements that have grown from a history of bias and discrimination, the stories told within it are ones of spirited girls and brave women; the male allies that have supported them; crushing setbacks, and triumph against the odds.

So here’s a whistle-stop tour of some of the key moments, starting at the beginning which is a surprisingly long time ago: 1628 is the first recorded match involving women in Europe. Not so surprisingly, it provoked outrage with a Scottish church minister on record denouncing the men and women he’d seen playing football together on Carstairs village green. But women carried on playing and wanting to play. Indeed, later into that century, accounts describe annual football matches involving fisherwomen of Musselburgh and Inveresk in East Lothian.

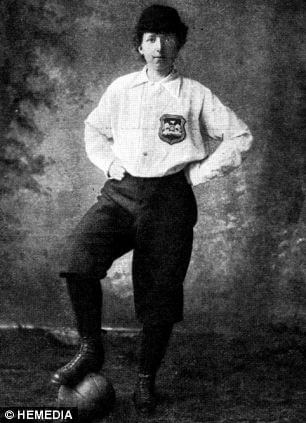

Helen Matthews aka Mrs Graham

In 1863, Association football was established in the UK, setting out the rules of the game. Women, keen to be involved but facing huge resistance, nevertheless persisted. In 1881 the first British women’s football team, Mrs Graham’s XI, was set up in Scotland by Helen Graham Matthews. Later that decade, a team of English women crossed Hadrian’s Wall to play them. A riot broke out in the 5,000-strong crowd, and shortly afterwards women’s football was outlawed across Scotland.

Then in 1884, The British Ladies Football Club was formed by Alfred Hewitt Smith, with the brilliantly-named Nettie Honeyball its captain and figurehead. Under the patronage of Scottish writer and feminist Lady Florence Dixie, the team was joined by Helen Graham Matthews of Mrs Graham’s XI. The team’s players were in the main from the middle classes, which along with Florence Dixie’s support, undoubtedly helped smooth its trailblazing passage.

On 25th March 1895, their first public match took place in London’s Crouch End between teams representing the ‘North’ and the ‘South’. The crowd was 10,000-strong with many more turned away. Media coverage was mixed. One report was relatively magnanimous in its observation that, “There seems no reason why the game should not be annexed by women for their own use as a new and healthful form of recreation.”

Another was grudgingly supportive as long as women didn’t get above their station: “Of course, if our women propose to harden the muscles of their limbs by fencing, football, and bicycling, no one need object to it, so long as they are willing to modestly keep themselves in the background”. The same writer reserved their outrage for the fact that tickets had been charged for, “…but when they charge gate money…and indulge in a game which was invented for males, and which can only properly be played by males, then it smacks too much of the ways of the so-called Pioneer Club, whose members believe in and preach the equal rights doctrine with men”.

British Ladies Football Club, 1895

It took a war to turbo-charge progress in women’s football in the face of such challenge, and so it was that WW1 ushered in a short-lived but progressive era. With men away, women working on farms and in factories began to enjoy a kickabout, teams and leagues were formed, and organized matches attracted huge attendances and raised large sums for charity.

Media coverage likewise became more even-handed, with women’s teams getting centre spreads in the Football Special Magazine alongside men’s, and reporters avoiding reference to women playing football being unusual in any way. There was even a weekly column by ‘The Football Girl’ in which she discussed the games and provided insight and analysis.

The culmination of this widespread uptake was the 1920 Boxing Day match between celebrated factory team Dick Kerr’s Ladies and St Helens Ladies at Goodison Park. It attracted 53,000 supporters with a further 15,000 turned away. Brands were keen to capitalize on its appeal; Lyons Coffee Houses decorated their cake boxes with pictures of women kicking balls. To the chagrin of many, these were signs that women’s football was now more popular than men’s.

This success could not survive the prevailing attitudes of the era; 1921 proved to be a pivotal year. On the one hand, every major town in England had a ladies’ team, with cities often having several. Demand had grown beyond matches for charity and spectacle, and there was an appetite for leagues, a governing body and for women to play professionally.

On the other, this was not to the liking of the establishment, who were concerned at the perceived detrimental impact the success of the women could have on the men’s game. And so came a crushing blow: in 1921 The FA banned women’s football, declaring the game “quite unsuitable for females”, and telling men they couldn’t let women play at their grounds.

Many applauded the move – one doctor was quoted as saying that kicking was too jerky a movement for women, and that “… just as the frame of a woman is more rounded than a man’s, her movements should be more rounded and less angular”; but others were appalled. As Major Cecil Kent, secretary of Liverpool FC, commented, “The thing I hear from the man in the street is ‘Why have the FA got their knife into girls’ football? What have the girls done except raise large sums for charity and play the game? Are their feet heavier on the turf than the men’s feet?’”

Over the coming years, much of the rest of the world followed suit – Norway banned it in 1931; France in 1932; Brazil in 1941; and West Germany in 1955. And in the UK, after something of a heyday, women’s football went underground for 50 years. It’s heartening that during this time there are, still, some remarkable stories – the ban did not mean women stopped playing. For example, in 1949, Percy Ashley founded the Manchester Corinthians to enable his football-obsessed daughter Doris to play. They went on to achieve great unofficial success overseas, winning a tournament in Germany in 1957.

Manchester Corinthians FC

But undeniably the half-century ban was a huge setback to women’s football in the UK. Finally, in 1971, The FA lifted the ban, and the game began its long journey of re-establishing itself. It’s worth noting at this point that just the following year, and having only just started playing the game, the US set the scene for their current-day dominance of it. They introduced a piece of legislation known as Title IX, which enforces gender equality, both academic and sporting, in high school and college education. It created a legal imperative that female athletes be given equal rights to federal financial assistance and is widely credited as the reason the US remain the dominating power in women’s football.

In the UK we began taking our own steps to repair the damage the ban had caused. In 1975 The Sex Discrimination Act was passed, making it easier for women to train to become professional referees. Other countries across the world were going on similar journeys, as the movement for gender equality gained traction. In 1980, Japan staged its first women’s tournament – albeit eight-a-side on mini pitches with children’s footballs, 25-minute halves and handballs permitted if they protected players’ breasts. Just a few years later, companies like Nissan began sponsoring teams in a new semi-professional league, and players were allocated office jobs allowing time off for training regimes.

In 1989, Channel 4 started to provide regular coverage of women’s football, and 1991 saw the first official women’s world cup – although ever-alert to the sensitivities of the male dominated football establishment, the words “World Cup” were avoided and it was delicately named, The First Fifa World Championship for Women’s Football. In a similar misstep, games lasted only 80 minutes. As then-US captain April Heinrichs drily remarked, “Fifa was afraid our ovaries were going to fall out”.

But progress continued. In 1997, the FA outlined its plans to develop the women’s game from grassroots to elite level. 2011 saw the inaugural season of the Women’s Super League. And finally in 2018, England had a fully professional women’s football league. The following year, Barclays were announced as title partner of The FA WSL, in what is believed to be the biggest-ever investment in UK women’s sport by a brand.

Which brings us to the FIFA 2019 Women’s World Cup, the most recent, global showcase of women’s football and a compelling indicator of how far it’s come since its earliest days. A record 28.1 million people tuned into the tournament in the UK via the BBC, watching superstar players such as the US team’s Alex Morgan and Megan Rapinoe; England’s Steph Houghton, Lucy Bronze and Ellen White; Brazil’s Marta (dubbed Pelé with skirts by Pele himself); host nation France’s Wendie Renard…and many more.

England Football Team – FIFA World Cup 2019

Phil Neville’s Lionesses had England football fans across the country enthralled as they stormed their way to the semi-final in a tour de force of footballing skill, drive and grit; and then heartbroken but still proud as they lost 2-1 to eventual champions the US. This most recent World Cup is not just significant because of England’s performance and the healthy viewing figures – 62% of which were reported to be male. It was also a commercial success. In 2020, the French Football Federation reported that hosting the tournament contributed roughly €284 million to France’s GDP, while every euro spent generated a return of up to 20 euros. The average financial contribution of each spectator – of which there were estimated to be over 1.2 million – was €142.

The fact that the women’s game can demonstrate return on investment is cause for celebration, along with the FA’s announcement in January last year that England’s men’s and women’s international teams are receiving equal pay. Women’s football has for sure come a very long way in the centuries since it began, with a formidable cast of characters – from village folk to fisherwomen, aristocracy to factory workers – paving the way to make possible what we have today.

There’s a lot to look forward to.